Tucson is only 70 miles from the U.S. border with Mexico, and the history in this area is rich with native peoples, changing land ownership with “New Spain,” and the missionaries who came to Arizona with “saving souls” for God in mind.

And therein lies a moral dilemma.

We had soaked up Tucson’s natural side with a visit to Saguaro National Park East and a trip up Mount Lemmon the day before, where the views and an unexpected wildlife sighting were thrilling starts to our touring.

Susan: “How about if I do this?”

After a quiet day “at home,” the next day, we then headed south toward what was once New Spain territory (along with Puerto Rico, Cuba, Florida, what is now the southern U.S., the Philipinnes, and Central America as far south as Costa Rica), then Mexico, but now part of southern Arizona.

Spain was big on evangelizing, and many missionaries were sent to its dependency, with San Xavier del Bac Mission (completed in 1797) being one of the churches that sprang up to bring the natives to Jesus. I’m not going to go all preachy, though I surely could. Instead, let the Mission’s plaques do the talking:

Jesuit Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino “served two majesties – the Church and the Crown. For the Church, the Mission saved souls and spread the Christian faith. For the Crown, they served as training grounds for native people to learn their assigned role as subjects of the King and citizens of a growing New Spain.”

“A mission was much more than a church; it was an entire community designed to teach European ways of life to people living on lands claimed by Spain.”

So much to unpack about that, isn’t there, when compared to the history of those “people living on lands claimed by Spain,” who had successfully thrived in the area for thousands of years. When I asked the docent at San Xavier what the Tohono O’odham tribe’s spiritual culture was like before the arrival of the missionaries, he said, “They were used to converting.”

We set all of that aside and entered each of two churches with the idea that we were experiencing historical places. Let’s take a stroll through San Xavier del Bac first.

The Mission’s property ends at the wall in front of it. The surrounding 71,095 acres are the San Xavier Indian Reservation, home to approximately 1,200 Tohono O’odham people.

The rainbow is an important image to the O’odham, signifying unity, among other things, so it was used in the entry’s archway.

It’s impossible not to notice the two animals flanking the altar. They look like weird cousins of those flying monkeys in The Wizard of Oz, but they’re really lions. Why so wonky-looking? Because the artists who created them had never seen lions, and only had a verbal description of a lion to work from.

The church honors Mary, mother of Jesus. Here, her dress includes an important O’odham concept through two embroidered “Man in the Maze” images, one on her gold vestment and one on her skirt.

Made of wood and without embellishment, this statue honors Kateri Tekakwitha, the only Native American to have been recognized as a Catholic Saint.

It’s a beautiful church filled with contrasts, arguably rife with cultural appropriation, and it has the devotion of those who worship here. It reminded us of a mission church we visited in Arizona many years ago, on a Reservation that was home to the poorest of the poor. When we commented on the immense wealth that could have fed the community and its children for decades, one of the parishioners said, “Yes, there is a great deal of wealth here, but we find solace and relief from our difficult lives in this place of such beauty.”

Who are we to say that’s wrong? Perspective matters.

Tubac – a little “village” of shops, restaurants, galleries, and a museum – was next along I-10, and we had a little wander and some lunch there. We try not to bring any more weight onboard Fati, so we admired the artists’ creativity, then headed south again.

Tumacácori National Historic Park features one of the areas other missions, the oldest in Arizona. Nearly 200 people lived here at one time, and the grounds included orchards, fields, gardens, homes, a “convento” (shared workspace and governmental center, not a nunnery), and a cemetery, as well as the church.

The bell tower on the upper right-hand side of the building isn’t a ruin. It was never finished, as the parish ran out of money before they could complete it.

Tumacácori makes no bones about what Spain’s mission was: “All aspects of daily life were subject to transformation – food, language, clothing, agriculture, and religion.” There is a term for that sort of “transformation” of entire groups of people, and as much as we enjoyed immersing in the history as we walked around, it was hard not to think about the O’odham’s lives before and after “transformation.”

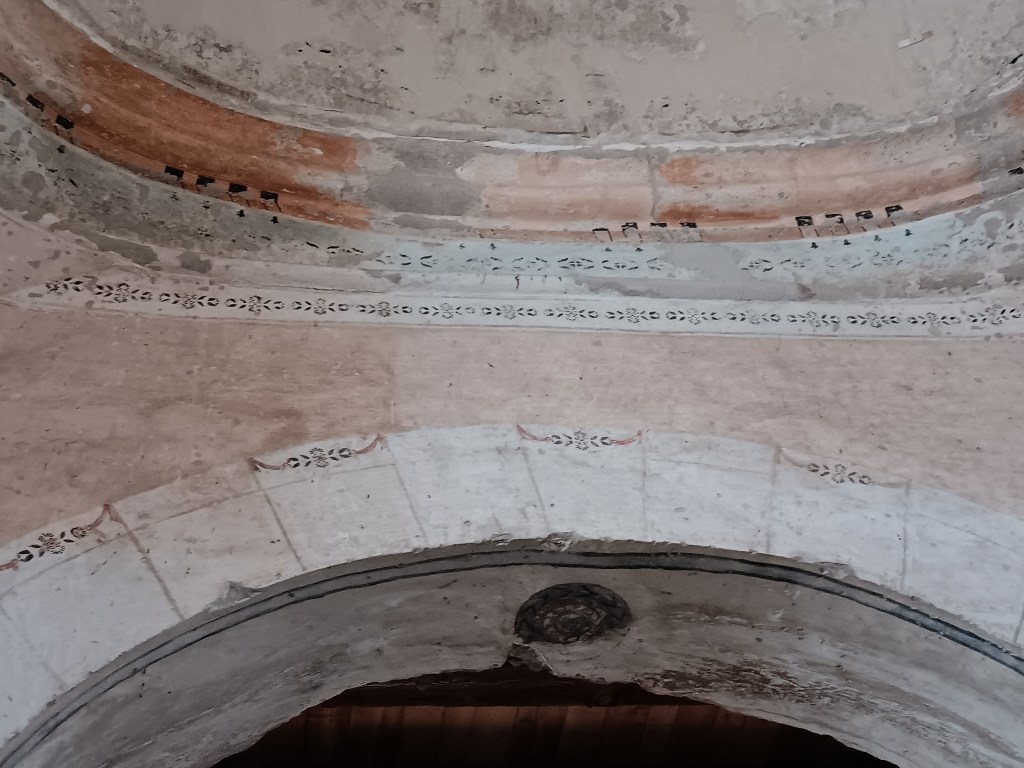

The Sanctuary was also painted and stenciled in bright designs, some of which can still be seen, albeit in faded form.

After Tumacácori was abandoned in 1848, the Sacristy became a refuge for cowboys, soldiers, Mexicans, and gold-rush era fortune hunters during inclement weather. Soot from their fires can still be seen on the ceiling, and their names are still on the walls around the door.

The cemetery bears silent witness to the devastation Apache raids and several epidemics wrought on the community. Most of the human beings originally buried here were children under the age of five.

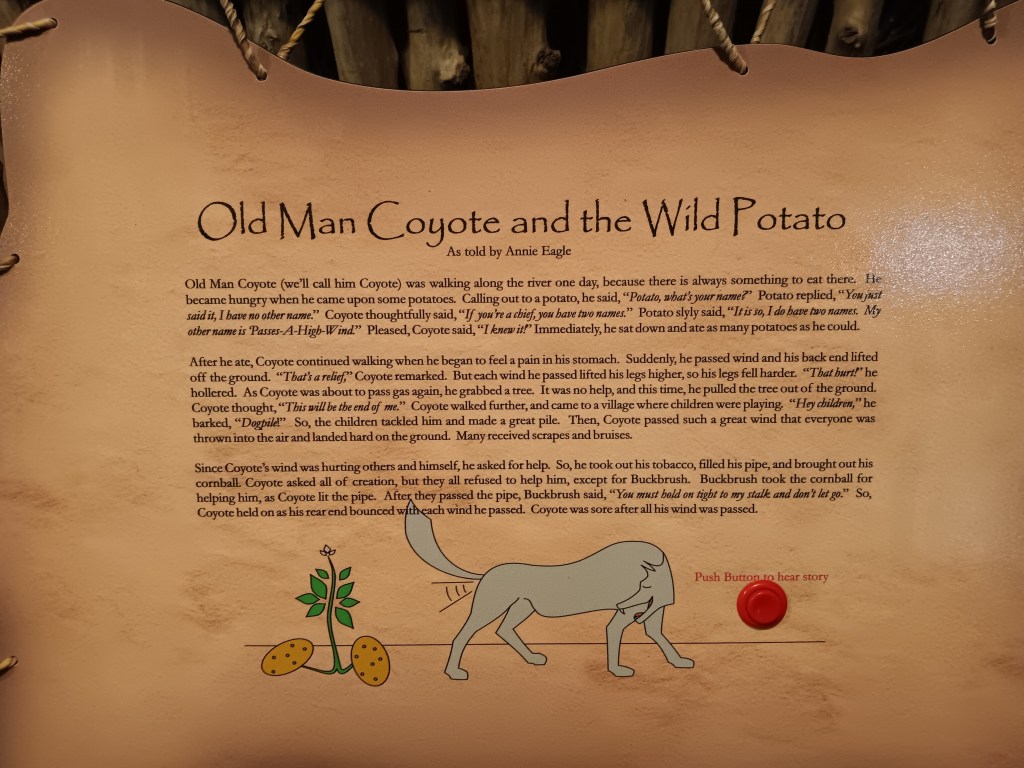

The ki – the O’odham word for house – provided shelter, while the outdoor wa:ato (brush enclosure) was the place for gathering together and for cooking. The O’odham still sometimes build homes from mesquite branches, ocotillo sticks, the ribs of saguaro cactus, and mud.

The convento was originally much, much larger. Built of adobe, most of the long, low expanse of it has slowly “melted” away. Now, only a small section (once a storeroom) is still standing.

The mission was abandoned for a year after an O’odham uprising against the Spanish and an intrusive neighboring tribe. Jesuit priests returned in 1753, were expelled in 1767, and were replaced by Franciscans who continued evangelizing until 1822.

The places we visit become a part of us, and, as small pieces of historical information are assembled into a greater picture, we find ourselves contemplating the story that greater picture tells.