Whenever we see a daunting mountain or endless rolling hills we think of the pioneers who made their way west with no smooth pavement to ease their rattling teeth and overworked horses or oxen. The Laramie Range at the southern edge of Casper, Wyoming was one such obstacle that proved the people who pushed westward let nothing stand in their way.

Two trails are famous in the U.S.: The Pony Express (Kansas City, Missouri to San Francisco, California) and the Oregon Trail (Independence, Missouri to the far reaches of Oregon). There were actually two more major trails, we came to find out, that cut their way through Wyoming: The Mormon Trail, which started in Illinois and ended in Salt Lake Valley, Utah, and the California Trail, from Kansas City, Missouri to many places in California). All of them passed through Casper.

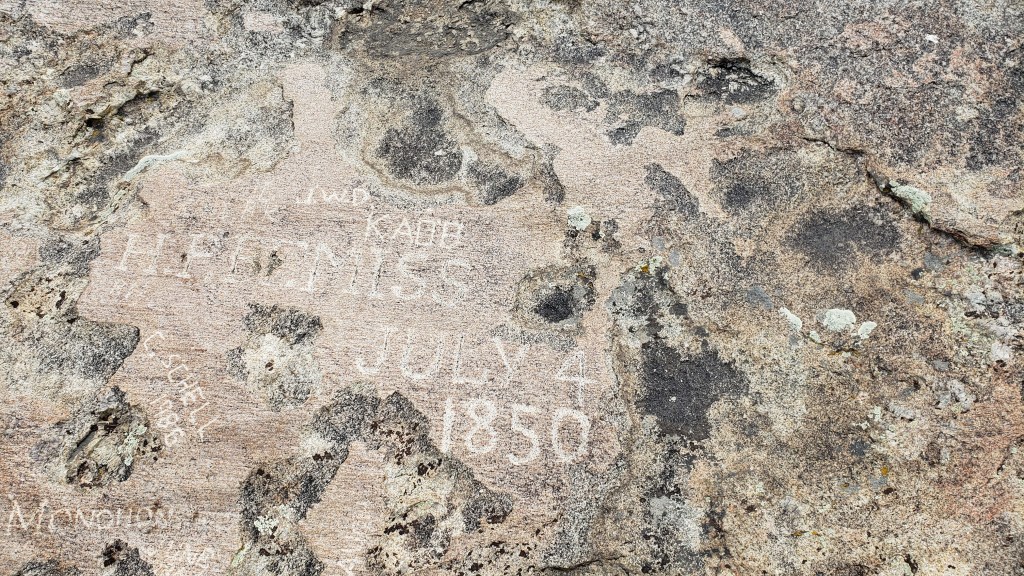

For some, it was a 2,000-mile journey from beginning to end, and it’s quite incredible that specific points along the way were used by all or nearly all of them. Independence Rock was one of the landmarks they looked for, and many left carvings on the hill that marked their passing.

Independence Rock was an importation milestone. Reach the huge granite mound by July 4 (hence, its name) and you’ve got a chance of surviving the rest of the trip. Arrive late, as part of the ill-fated Martin Company Morman handcart expedition did, and disaster is the likely result.

Martin’s Cove, ten miles to the east, tells the 1856 Morman Handcart Disaster story. Under the guidance of the Edward Martin Handcart Company, the season’s final two (of five) English emigrant groups departed Iowa City, Iowa in late July. By mid-October, having been delayed by snowstorms and suffering from illness, fatigue, and malnourishment, 50 of them were dead. It became the greatest single-event loss of life of the country’s entire western migration.

Another geological landmark the westward expeditions looked for was Devil’s Gate, near Martin’s Cove, a gap that allowed them to travel south of the area’s impassable river gorge. All four “trails” passed through this gap, and their wagon and handcart ruts are still visible. We couldn’t see them, nor the former Martin’s Cove camping site the travelers used, because (say it with me…) NO DOGS are allowed on the trails.

A third landmark was Split Rock, a camping and grazing site one-day’s travel (12 miles) from Devil’s Gate, distinctive for the enormous V-shaped “split” (more like a natural cut-out) at the top of the mountain. You’ll see it slightly to the left of the middle mountain’s center in this photo:

When we moved Fati to a new campground in Wheatland, Wyoming, north of Cheyenne, we made a day trip out to the Guernsey Ruts, Register Cliff, and Fort Laramie, also milestone locations on the trails.

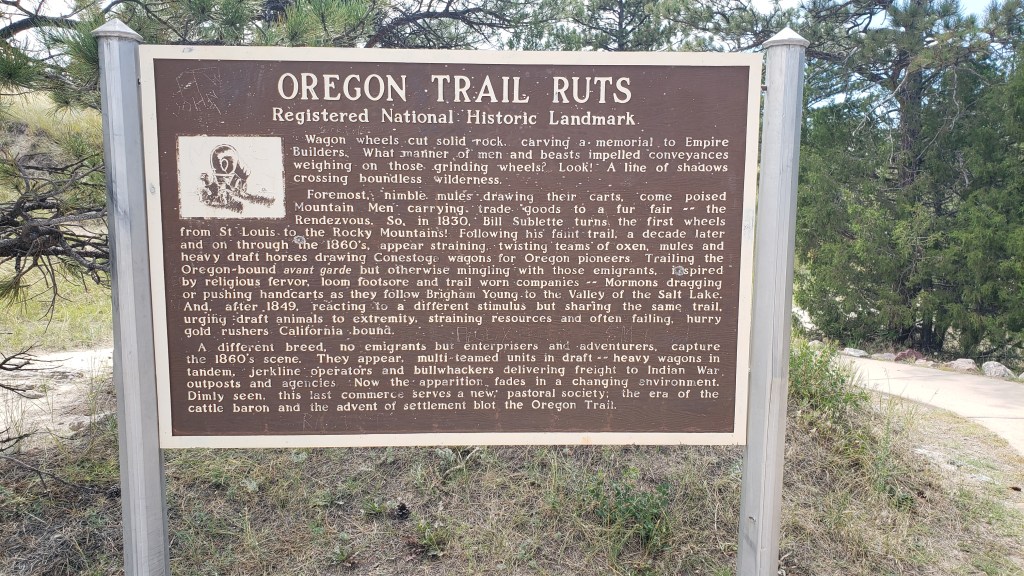

The Guernsey Ruts are located at Oregon Trail Ruts State Historic Site, where wheel tracks made by covered wagons and handcarts left deep gashes in the soft sandstone, which are now on protected land. Some are five feet deep, and it’s easy to see the wheels’ furrows and the deep pathway where people walked next to their wagon.

Visitors to the site are allowed to walk in the hard tracks, and we really felt a human connection to the slow, difficult climbs and drops the pioneers experienced as they plodded their way west. More than 500,000 pioneers crossed here due to the topography of the land, which is why the ruts are so deep.

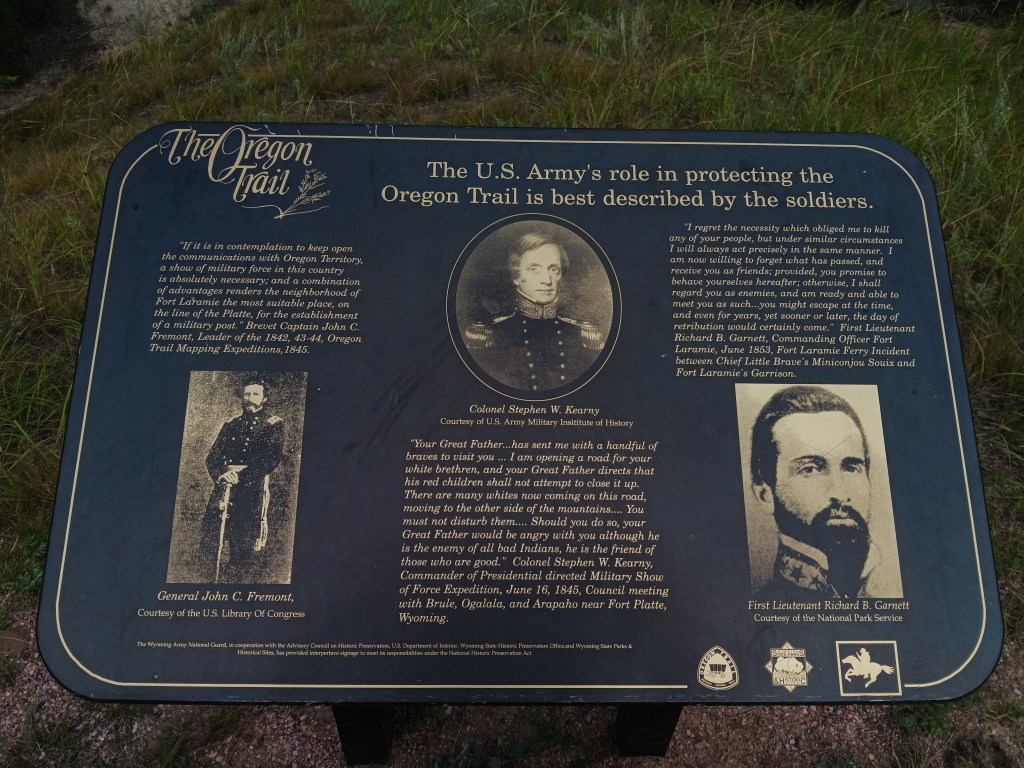

The one blot on this otherwise evocative site is the panels that tell the story of the trail only from the perspective of the soldiers tasked with “protecting” the emigrants’ passing through land that was home to native tribes. In a nutshell, the sentiment was that the tribes were hostile and it was perfectly fine to kill them “as needed.”

There are a few sites we’ve seen that give a nod to the people who actually lived on the land before white people came through, and their desire to continue living peaceful lives, but so far they’re certainly the exception. It’s impossible not to see these plaques’ quotes as a conscious choice.

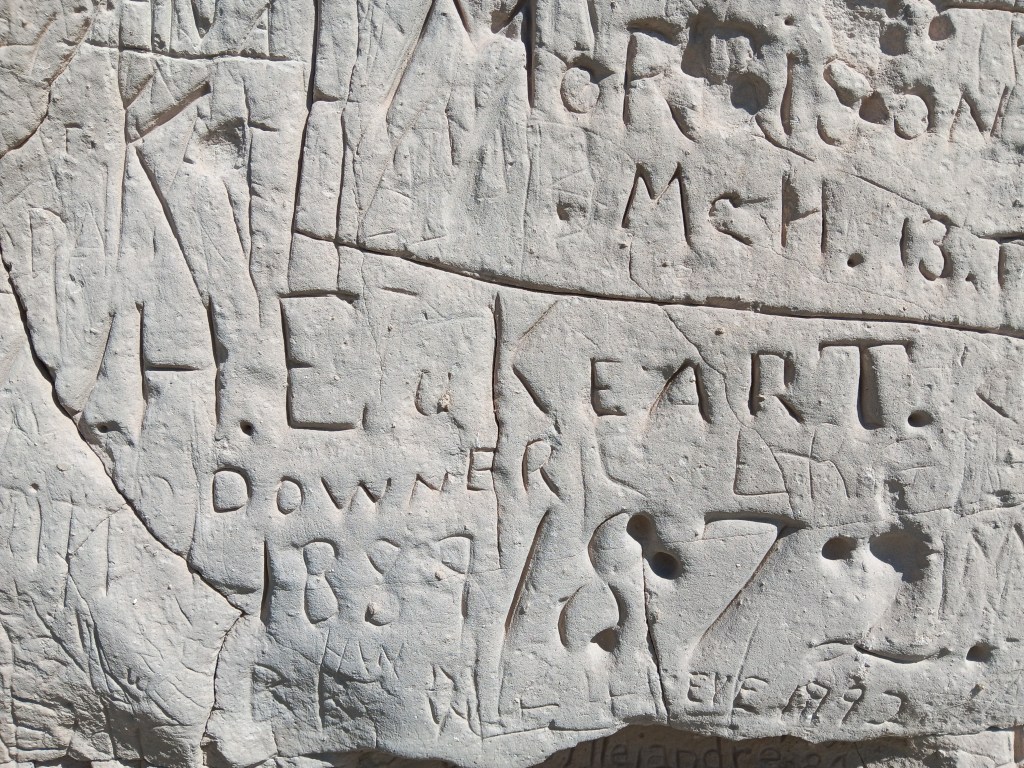

Register Cliff is about 12 miles east of the Guernsey Ruts, and it also holds the title of a State Historic Site. Here, trappers, fur traders, and emigrants rested during their journey west, and some carved their names and the date into the 100-foot-high limestone cliff.

We didn’t see the earliest dates that have been identified on the cliff (1797 and 1829), nor did we see petroglyphs and pictographs made by the native people long before white people arrived, but we did see some carvings from the mid- to late-1800s, and many carvings behind a fenced area are from the time the Oregon trail was heavily used.

Fort Laramie – founded in 1834 as a trading post before evolving into a military post in 1849 – wasn’t the stockade-style fort we expected. Instead, it was more like a mini town, with necessities of daily living such as a bakery, a jail, a schoolhouse, barracks, and officer homes. It felt a lot like a military-specific version of Dearborn, Michigan’s wonderful Greenfield Village.

It was a place where emigrants stopped on their way to Oregon, Utah and California, as did some local tribes, to trade furs and hides for other goods. It was also a stop for the Pony Express from 1860-1861.

We’re certain we’ll see a lot more sites having to do with the settling of this great, vast country, and when we do, we’ll be happy to share them with you.